by Bernardo Naranjo

This blog is part of a DeliverEd Initiative series by policymakers and leaders from around the world who share their challenges in delivering reforms and reflect on the various approaches used to solve these challenges in their countries.

DeliverEd aims to build the evidence base for how governments in low- and middle-income countries can achieve their policy priorities in education using delivery approaches.

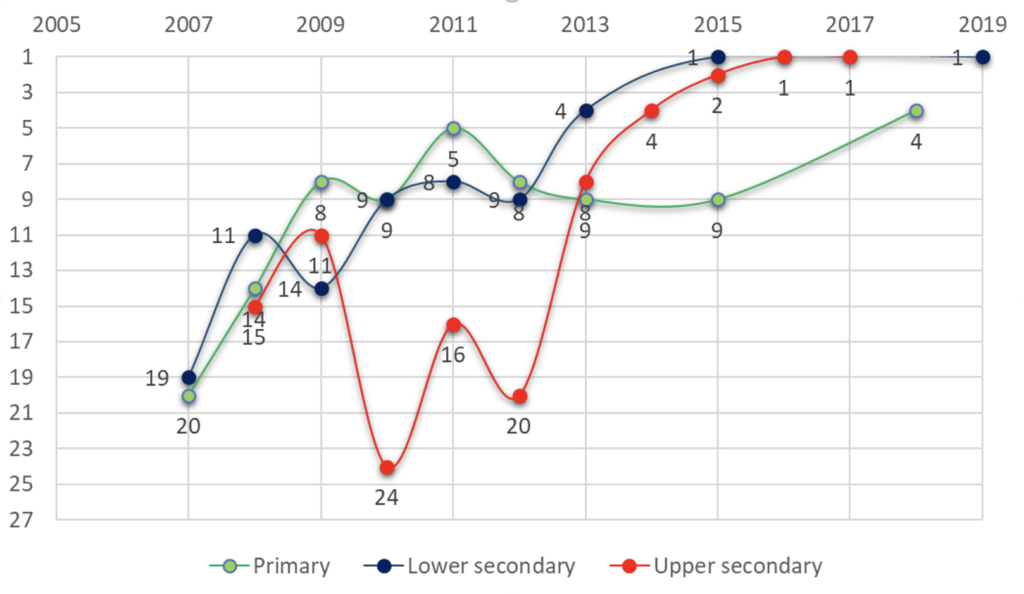

In 2011, a new government of Puebla started a six-year term with very high aspirations to improve education for the more than six million people in this central Mexican state. As the fourth state (out of 32) with the highest percentage of poverty in the country at the time, Puebla was normally near the bottom for most indicators. In an unusual move, a senator stepped down to become the head of the Secretaría de Educación Pública de Puebla (SEPP), with the responsibility to lead a system with more than 1.9 million students and 95,000 teachers in over 14,000 schools.1 He invited a group of able professionals from all over the country to join SEPP, including organizations like ours. Six years later, Puebla was recognized as a national reference, with the top spot in the national standardized students’ assessment (PLANEA) at both lower and upper secondary levels (Figure I); rising attendance and retention indicators; and a number of innovations taking place with wide support from teachers, researchers, and organizations in Mexico and abroad. What did we do?

Figure

I PUEBLA

State rankings in national standardized assessments

Source: De Hoyos, Rafael & Naranjo, Bernardo “Uno de los sistemas educativos más exitosos en América Latina. El caso de Puebla en el contexto internacional”, Este País, Oct 27th, 2020

Improvement is a combination of clear objectives and strategies, but also a great deal of craftmanship. No recipes and no shortcuts. While dealing with school systems, every strategy and every action must be adapted to local circumstances. Listening to people, building strategies with them, and following up closely are key. Details normally ignored were nowconsidered in a careful implementation process to make a difference.

Our experience as a private organization helping public education in Puebla was very challenging but immensely rewarding. When the administration started, we found the normal reluctance to listen to external players: officials and other authorities wondered how a group of outsiders could help those in charge for years. We were received with a “done-that” attitude, and they were right most of the time. We needed to start from scratch, and initially we worked mostly with lower-level officials to show we could be helpful. Patience proved very effective. At the end of the administration, our organization was referred to as “the advisors” and considered part of the SEPP leadership team. Without the burden of the many administrative and political duties public officials have, we were fully committed to following up ongoing actions, listening to SEPP officials and teachers, visiting schools, finding new opportunities, and promoting the state policy at the national and international levels. Puebla became an education policy lab frequently visited by other states’ officials, NGOs, and international organizations.

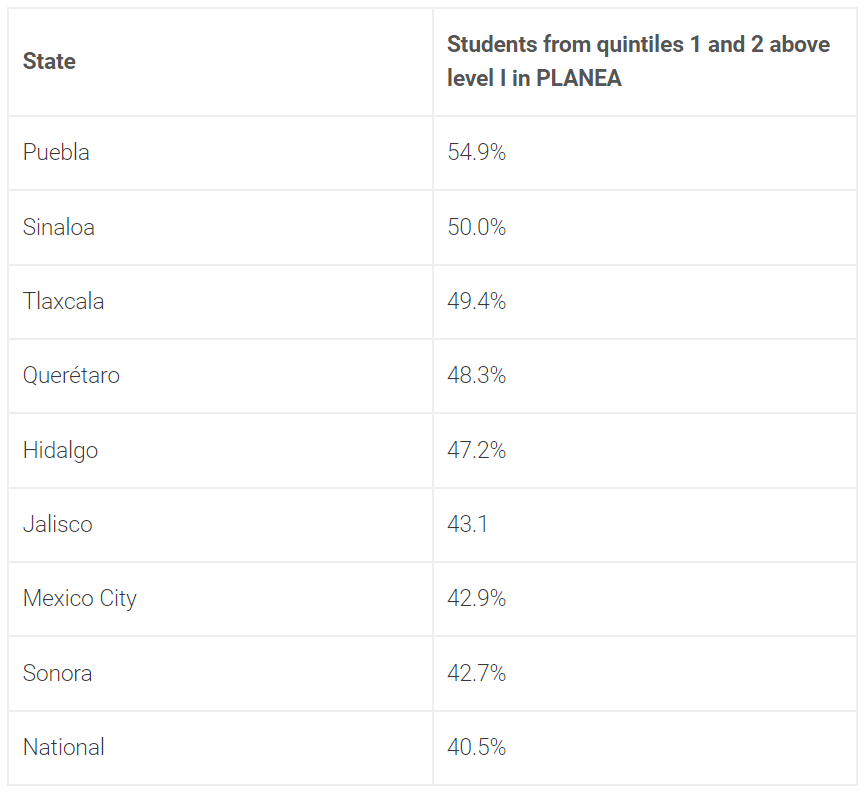

Listening to stakeholders and including supervisors and other mid-level officials in every strategy was central for success and for sustainability as well. We worked hard to include them in both the decision-making and implementation processes, especially those from low-performimg schools. As a result, good results continued even after our participation ended: in 2019, students from the lowest quintiles still had a clear lead when compared with those in similar schools nationwide (Figure II).

Figure II

ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT AMONG LOWER QUINTILES

PLANEA results among students from quintiles 1 and 2

Lower secondary education, Mathematics 2019

Source: With data from Planea 2019, Lower Secondary Level

We found the following elements very useful while working with different states in Mexico and all of them were part of our experience in Puebla:

1. Leadership’s willingness to succeed, with the capacity to innovate and implement. Although this seems a rather logical requirement, these virtues are less common than they should be.

- High aspirations in the organization. We insisted that origin is not destiny, and that improvement was possible if people believe it and act accordingly. Puebla’s status as one of the poorest states in Mexico was a constant issue to overcome.

- Top levels in the organization placed high priority on implementation, and maintained direct contact with schools and teachers. People became “goal oriented” instead of only praising “good efforts.”

- Leadership created a friendly environment for innovation, giving serious consideration to new ideas and considering some mistakes as normal steps for improvement.

2. Clear, basic objectives with an education model as a reference for decision-making. With hard-to-dismiss and easy-to-communicate objectives, we adapted the experience from Ontario to look for attendance, graduation, and learning as priorities (APA Model):

- Attendance (Asistencia) at school of every person 3 – 17 years old. In 2015, about 250,000 of a total 1.8M people in this age range were out of school in the state.

- Graduation (Permanencia) of every student from upper secondary education. If retention and transition rates continue the same, only about 61% of primary school new students would graduate.

- Learning (Aprendizaje) at least the minimum acceptable content in Spanish and math, according to the national assessment PLANEA. In 2017, one-third of students in 12th grade in Spanish, and two-thirds in math did not achieve this goal.

3. Well-defined strategies:

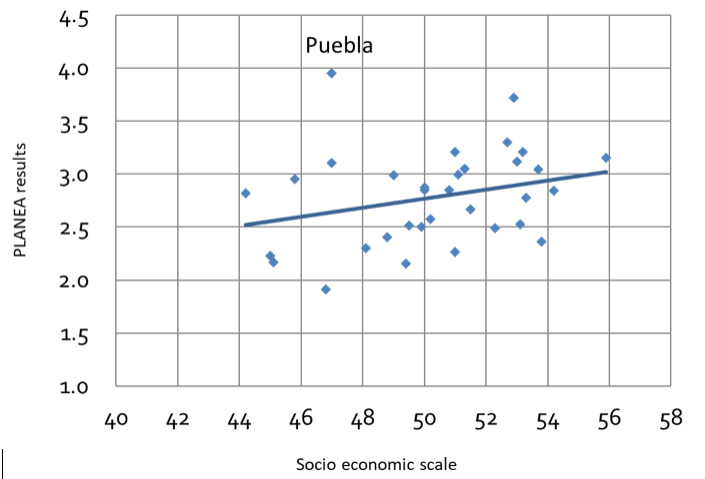

- Targeting schools using national assessments (PLANEA). To ensure effective support, we only chose between 100 and 200 low-performing schools per level each year, with 100 or more students, (in order to increase efficacy and reduce teacher turnover risk) that were willing to participate. Most low-performing schools serve students with low socioeconomic status, thus making a strong impact on equity (Figure III).

- Coordinating efforts to make the most of all available resources. Institutions, education levels, programs, and resources were articulated so they worked with a common set of goals.

- Careful implementation and follow-up processes, to make sure everyone participating understands her/his role and identifies mistakes and opportunities for improvement.

Figure III

ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT AND SOCIAL ECONOMIC STATUS

PLANEA results and socio economic level by state

Upper secondary education mathematics 2017

4. Collaborative decision-making processes to ensure legitimacy and improve implementation:

- A top-level board was established to meet periodically and coordinate different offices in the process. Technical level groups for specific processes (dropout prevention, supply analysis, teacher training, evaluation, information) were created to help design and implement actions.

- Schools were able to decide specific actions for improvement, aligned to the common objectives. Each school had its own quality coordination, usually with the best teachers.

- Partnerships between schools were encouraged, so low-performing ones could exchange ideas and receive advice from neighboring schools.

- Direct contact with teachers and principals was important: school visits, focus groups, and surveys.

5. Efficient teacher training with an emphasis on quality, not quantity:

- Facilitators were properly trained and recruited locally among the best teachers, principals, or supervisors. They provided relevant training to their colleagues at a very low cost.

- Groups were limited to 25 teachers or less, and courses were in-person.

- Content was centrally designed by specialists, ensuring that specific needs and opportunities were addressed.

6. Formative assessment to identify priorities at the state/region, school, and classroom levels

- At the school, region, and state levels, results identified teachers and topics with urgent need for support.

- The technical group responsible for evaluation processes created a platform to help students practice exam-like exercises.

- Standardized assessment results were required to have some impact on grades. Every teacher decided how much, but this gave students an incentive to perform at their best and achieve a solid diagnostic.

7. Tools to improve school management and help them have a stronger orientation towards academic rather than administrative matters:

- Customized information was distributed every other month to every school (Reporte APA), with statistics, indicators, and academic results, but also identifying by name every at-risk student, as well as the specific topics in math and Spanish with lowest results in PLANEA.

- Supervision strengthening. The best supervisors were chosen to create the Academia Poblana de Supervision, that became a consulting reference for the Secretary, and helped train the roughly 950 supervisors in the state.

- Ease the administrative load to schools, as they were continuously required to do unnecessary paperwork.

8. Structure adapted to priorities and not the other way around. Some examples:

- One undersecretary for all K-12 education was created to improve coordination. The SEPP grew at the beginning of the administration, but it became clear later that a more compact organization was cheaper and more effective.

- Comité Estratégico de Educación Obligatoria, an executive board with top officials, was established to meet weekly, make decisions, and follow up on improvement programs.

- The Servicio de Asistencia Técnica a la Escuela de Puebla (SATEP) was an effort to reorganize regional staff for better coordination of teacher training activities statewide.

- Unidad de Promoción del Derecho a la Educación (UNIPRODE) was created to coordinate statewide efforts to prevent dropouts and bring out-of-school kids back.

These ideas should not be copied: principles, strategies, and actions should be adapted to new settings and complemented by local initiatives to create a new, unique improvement experience. Clear goals, follow-up mechanisms, and long-term thinking are the most valuable resources an education system can have, along with a passionate leadership team dedicated to helping people grow in the best possible way.

Bernardo Naranjo has worked with education systems for 25 years as a public official, researcher, professor and policy advisor. He places an enormous value to the collective construction of solutions, where teachers, families and school leaders must play a substantial role. Taking advantage of the systems’ own strengths and building local capacities are also big priorities in his work.

He founded in 2006 Proyecto Educativo, an applied research and consulting firm in Mexico. In the state of Puebla, this organization had a central role in the most impressive improvement seen in a Mexican state since evaluations were established (2011-2017). That included building its own policy model; designing the academic stra¬tegy; following up the implementation process; and even obtaining substantial external funding for those activities.

Other remarkable achievements of Proyecto Educativo include helping the teachers of the state of Sonora achieve the top spot in the national appraisals (2016); saving over 2M paperwork hours a year to schools in Coahuila (2020); and increasing preschool new entrants in Sinaloa even during the pandemic (2021), to name a few.

Bernardo (Stanford PhD, UC Berkeley MPP, U Iberoamericana BA) was a Board Member at Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación Educativa (INEE), representative of Mexico to OECD’s PISA, and has been honored with the Alumni Excellence in Education Award by Stanford University.

1 K-12 enrollments in Puebla are almost twice those in Finland

2 In 2003, a new government in Ontario adopted two initiatives: the Literacy and Numeracy initiative, to increase reading and mathematics outcomes in elementary schools; and the Student Success initiative, to increase the high school graduation rate to 85%. Both were very successful. OECD, “Ontario, Canada: Reform to Support High Achievement in a Diverse Context”